"Strange the obsession that an imaginative woman can exercise over an unimaginative man. It the sort of thing that can follow a chap to his grave."

One of the more unusual offshoots of collecting supernatural fiction is hunting for the numerous editions of one short story or novella published as a single volume. Lovecraft's The Shunned House, the horror author's first work to be published in book form, is such a volume. Not so elusive as it used to be, but exorbitantly expensive should you find a copy in an antiquarian bookshop. There are other more readily obtained books and much more affordable and often much more interesting as both entertainingly creepy genre fiction as well as well written literature. The Half Pint Flask by DuBose Heyward belongs to this other category. I recently re-read it for our monthly "Friday Fright Night" meme hosted by Curt Evans and a found it to be as chilling and evocative as I did when I first read over twenty years ago.

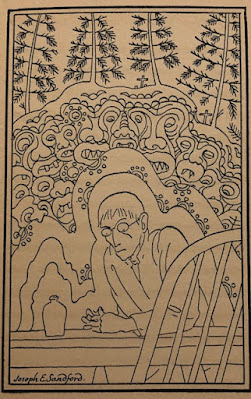

The book itself was handsomely produced in both a limited numbered and signed edition as well as a trade edition. Both editions are fully illustrated with three full page black and white line drawings by Joseph Sanford as well as head and tail pieces and numerous vignettes. Of the two editions the latter is much easier to find but not so easy to find with its exceptionally scarce dust jacket (see photo above, courtesy of Eureka Books in California). I only learned of the fine binding in a limited and numbered edition when I went looking for the first edition dust jacket. My copy is a serviceable reading copy, jacketless with rather worn boards but with pristine pages inside. It was very cheap when I bought it two decades ago and you'll be hard pressed to find a copy without jacket for under $25 these days.The story is a fable of sorts teaching a lesson about respect for the dead, the sacred nature of cemeteries and ultimately a cautionary tale to greedy collectors of curios and objets d'art. DuBose Heyward, an expert on his home state of South Carolina and its native Gullah community, incorporates African legends and mythology, Black American superstition and funereal rituals, a tinge of witchcraft, and one appearance of a ghost. Its 55 pages tell a tale of collector's mania, desecration of a grave site, covetousness of a rare antique glass flask, and retribution from the ethereal world. The sections on African mythology and religious rites that mix with a suggestion of black magic are eye opening and rendered with a flair for authenticity without ever seeming sensational or lurid. Heyward had deep respect for the Black community of his home state and was fascinated with the Gullah culture, its language and customs. The reader learns quite a bit about the Gullah world in the telling of his tale.

The Half Pint Flask (1929) is narrated by Mr. Courtney, a writer of fiction, who plays host to Barksdale, a would-be anthropologist who has traveled to Ediwander Island in South Carolina Gullah country to write a "series of articles on Negroid Primates." The term annoys and angers local Courtney who describes Barksdale's demeanor and tone: "Uttered in that cold and dissecting voice, [the phrase] seemed to strip the human from the hundred or more Negroes who were my only company..." Courtney goes on to explain that the local Blacks are descended from the slaves who worked the largest rice plantation in South Carolina and that their isolation may seem have kept them "primitive enough." This provides even more incentive for for Barksdale's impending research.

On route to their lodgings the two men pass by a cemetery reserved for burying the Blacks. The gravesites are covered with "a strange litter of medicine bottles, tin spoons, and other futle weapons that had failed in the final engagement with the last dark enemy." Barksdale has the eagle eye of a manic collector and he immediately spots a treasure. We learn he is a collector of antique glass, in particular a rare type of glassware found only in South Carolina. He orders the carriage to stop and races to the gravesite where he plucks the glass flasks from the mound and brings it back with him.

"Do you know what this is?" he demanded, then rushed triumphantly with his answer; "It's a first issue, half pint flask of the old South Carolina state dispensary. It gives me the only complete set in existence. No another one in America."

Courtney warns his fellow writer that he ought not to mess with the graves of the local Blacks. The objects placed on the graves are as sacred to them as the remains they protect. He pleads with him to put it back immediately. But Barksdale will not hear him, dismissing all his warnings as superstition and nonsense. He assures Courtney he will offer a good sum to whoever placed the flask on the grave. Unfortunately, he never follows through with that empty promise. It is his undoing.

The rest of the story details the aftermath of Barksdale's rash act and disregard for the traditions and beliefs of the locals. Eerie sounds and thundering seem to descend upon the house where he and Courtney are staying. The droning and weird vibrations that infect the household cause insomnia and headaches. Drumming and singing, strange chants fill the night air:

I have always had a passion for moonlight and I stood long on the piazza watching the great disc change from its horizon copper to gold, then cool to silver as it swung up into the immeasurable tranquility of the southern night. At first I thought the Negroes must be having a dance, for I could hear the syncopation of sticks on a cabin floor, and the palmettos and moss-draped live oaks that grew about the buildings could be seen the full quarter of a mile away, a ruddy bronze against the sky from a brush fire. But the longer I waited listening the less sure I became about the nature of the celebration. The rhythm became strange, complicated; and the chanting that rose and fell with the drumming rang with a new compelling quality, and lacked entirely the abandon of dancers.That night Courtney beholds the vision of Plat-eye, a legendary figure of the Black community based on a African god of vengeance. "Plat-eye is a spirit which takes some form which will be particularly apt to lure its victims away," Courtney has earlier explained to Barksdale. It is clearly a foreshadowing of the climax of the book.And Barksdale himself becomes a haunted man in the worst way. His mania for glass has turned a fascination into a curse. His flouting of the very subject of his writing which is filled with facts about the "deeply religious nature of the American Negro" results in a deadly lesson for the fatuous writer and puts an end to his collecting and studying for good.

|

| DuBose Heyward, 1929 (photo by Ben Pinchot for Vanity Fair) |