Samantha Heather Mackey (see that wink-wink allusion to the Daniel Waters’ screenplay?) is the protagonist, an MFA candidate and the outlier in a coterie of young women all seemingly clones of each other. Her fellow writers call themselves Bunny and are the most obnoxious clique ever to have been created in either novels, TV or movies. Their saccharine sweet adoration of one another outdoes the clinginess of the Heathers. Samantha loathes them but of course secretly wants to be part of the group. And so when seemingly out of the blue Samantha is invited to a private writing workshop the Bunnys call their Smut Salon she accepts against her better judgment and the advice of her best pal Ava.

The Smut Salon is an extension, albeit a soft core porn version, of the pretentious nonsense they are subjected to in their writing seminar. In essence it's nothing more than a sharing of sex stories, but the kind of giggly girl stories you’d get from inexperienced pre-adolescents, not young adult women in graduate school. The Smut Salon is only one aspect of their life outside the classrooms. As the novel progresses, we discover their desires and obsessions with creativity manifest in sinister rituals that defy the outrageous spell work seen in TV shows like The Craft, Charmed and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. This is the work they do in Workshop, capital W mandatory. The Bunnys are toying with a supernatural method to create life and in keeping with their Smut Salon obsessions they keep creating young men. They are not referred to as boys, however. To the Bunnys they are Hybrids or -- fittingly -- Drafts, mere works in progress as befits the work of a writing Workshop of course. And in the maddest bit of twisted imagination Awad has them create life from another form. The word "alchemy" is overused in MFA programs to discuss the supposed magical quality of writing fiction and Awad grabs a hold of that transformation metaphor and turns it into an absurdity. The Bunnys create life from their own namesakes – cute rabbits they capture from the bunny infested campus grounds.

I told you this was bonkers! It’s also deliciously creepy and madly funny and at times sorrowfully moving.

The catch to all this delving into the dark side of creation is that the Bunnys are not very good at either writing or creating life. In Samantha they see their opportunity to bring someone better at creation into their fold and test her. On the surface however, they belittle her work in the seminar and they make it appear they are going to model shape and improve her underappreciated talent outside of the classroom. We all know that the reverse is true. That just as Samantha envies the close knit friendship among these clannish clones they also envy her outsider status, her individuality and her darkly attractive fiction that actually has a plot.

Awad’s brilliant ironic touch is shown in the men the Bunnys conjure from cute rodents. On the outside they may be gorgeously handsome and resemble movie stars, athletes and rock musicians the girls fantasize having sex with but they are broken and flawed. Their hands never fully form nor do their genitalia. And so they appear to the Bunnys in handsome blue designer suits but wearing black gloves to cover their stumpy clawlike paws. They are never able to actually touch the girls with real fingers or fulfill their desires with a real sex act. It’s a brilliant touch on Awad’s part. Just as the Bunnys passive aggressively critique Samantha’s writing for lack of a character development these girls clearly haven’t mastered that skill in their attempt to create human life in their gory rituals.

When it’s Samantha’s turn to whip up a Hybrid or a Draft she not only surprises herself but shocks the Bunnys. It’s the beginning of the end of the group, a sinister revenge begins to formulate far beyond the reaches of Samantha’s own warped imagination. And the Bunnys never see that the tables have turned and they are being victimized at their own games and rituals.

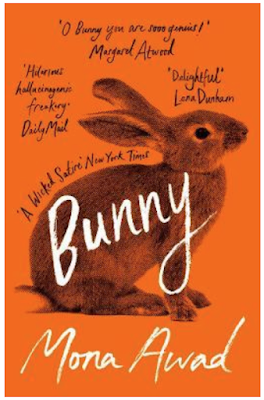

Bunny seems at first to be just another academic satire. Mean Girls Go to College, might be an apt subtitle. But those rituals change the entire focus of the book. At first I was utterly bamboozled by the fantastic elements of the Hybrid Workshop and the strange literature quoting things resembling good looking young men. It’s this linking of creative writing with creating life as a wish fulfillment for desire and love that makes the book worthy of attention. In years to come I imagine that Bunny will achieve the kind of cult classic status as similar books that explore twisted creation and perverse pursuit of love like the still noteworthy, unclassifiable novel of the fantastic Geek Love by Katharine Dunn.

Bunny has been compared to Heathers, The Secret History by Donna Tartt, and the movie Jennifer’s Body. Awad’s book has so little in common with those other works. The Heathers analogy is obvious of course, but this book is not so much about individuality vs. group identity or the need to belong or popularity or anything remotely like that. It’s really about the dark force of untethered imagination, the danger of an indulgent fantasy life. Why no one has ever mentioned Frankenstein, Geek Love, or even the charming fantasy novel Miss Hargreaves is beyond me. Ultimately, Bunny is simultaneously a love letter to and a dire warning about the power of imagination. For any person who has ever heard a parent, a friend, or anyone say “Stop pretending!” or “Get your head out of the clouds” or any number of warnings to snap out of it and get back to reality Bunny has a lot to offer, a lot to teach. Real life can be so much more rewarding if we only open our eyes and see what’s right in front of us rather than imagining what we think might be better for us.