First off, and granted this spoiled my enjoyment of the book as a whole, was the choice of translator Joan Tate to Anglicize the entire book. Death Awaits Thee takes place in a thoroughly Swedish locale -- the very real Drottningholm Theater built in 1766, a marvel of Swedish architecture and European history and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's one of the only theaters in all of Europe that still retains original 18th century scenery pieces and restored hand-operated theatrical machinery of that era. Photographs of the theater flood the internet, stories of visits to this historic place also appear by the hundreds in all languages. It's worth trawling the internet and reading some of the better posts and articles if you have time. With a murder mystery redolent of Swedish history and atmosphere one would hope that the book would stay thoroughly Swedish. But it hasn't.

1. All references to Swedish currency have been changed to pounds. What a hassle it must have been to convert the money amounts. Or did she even bother with that? An amount of 800 pounds is missing during the story and is somewhat crucial to the plot. But is it actually 800 pounds? Or was it 800 krona and the translator simply substituted pounds without bothering to calculate the British equivalent?2. The character names -- with the exception of Puck Bure, Lang's female protagonist and not-so-good amateur sleuth, and an opera singer named Jill Hassel -- have all been changed to easily comprehended British names. This infuriated me. For those interested the English names are Teresa, Diana, Stephen, George Geraldson (whose surname is also changed), Richard, Matthew and Edwin. See the photo below for the real names Maria Lang gave her cast of characters. I found an online version of the original text from which I took several illustrations for this post. You can match the names to see how Tate robbed them of their real identity. I've typed the British substitutes above in the order they appear in the list below.

3. And this is the most upsetting part -- the translation itself is a pretentious Anglicization of awkward syntax, heavy use of British idioms and vernacular in the dialogue, and other elements that take you out of the Land of Lingonberries and Pancakes and transport you to the Land of Bangers and Mash.

In the long run Joan Tate and the editorial staff of Hodder & Stoughton have fairly ruined the book by wringing nearly all that is Swedish from its admittedly thin pages.

|

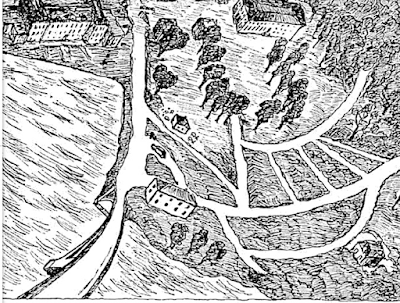

| The thunder machine as depicted on rear cover of Swedish edition |

The plot concerning a production of Cosi Fan Tutte and a murdered opera singer, her body found crushed and disfigured in special effects device known as the "thunder machine," offers the reader a smattering of mysteries not the least of which is how was she actually killed and why was she carried up to the machinery-laden attic and shoved through the small opening of the effects device. Motives are aplenty and tend to revolve around the impassioned and egocentric actors we find in theater mysteries. Jealousy, envy, hatred -- you name it, it's here.

But as for clues? Or the fair play aspect that one would think would be present given Lang's comparison's to her heroine and the writer she attempts to imitate? Few and far between. I can only recall two real clues!

Too much of the story comes far too late in the book. Prior to the arrival of Christer Wijk (surname altered to Wick in this "translation"), who appears only in the final two chapters, we are treated to intensive back story among the theater troupe and the rambling fantasies of Puck who is tempted to have an affair with Matthias Lemming, the opera conductor. The murder investigation is conducted by a non-series detective and his team. Then when Wijk finally appears he interrogates the characters for a third time (!) recalling the work of Carolyn Wells. I wonder if Lang read any of her books. In the end this felt more like a Wells novel than any other woman mystery writer Lang has been compared to. The suspects lie and withhold information just like Wells' characters and are coerced or manipulated into finally telling the truth when Wijk shows up. He does no real detective work at all. He relies on what his predecessor and police team have already done, notices discrepancies in stories, then simply gets people to tell the truth. And like Wells' "transcendental detective" Fleming Stone, Wijk subsequently intuits and guesses using "psychology" to ferret out the murderer. In the end the killer delivers a long confessional monologue, once again just like the majority of Wells' mystery novels. It's all disappointing, a real let down with all this questioning and re-questioning.

To be fair there are elements that I admired like when conductor and production director Matthias Lemming tells the full story about his volatile relationship with his ex-wife Tova, the murder victim. I also liked the characters of Ulrik and Jill who were the most lively out of the bunch of opera singers. Ulrik is Lang's token gayboy character and Jill is the mean-spirited bitch of the opera company. I guess it's always fun for writers to indulge themselves and let go of their reins when writing these types of characters. Lang certainly enjoyed those two for their scenes always enliven the tone of the book.

|

| Maria Lang, circa 1950s |

Death Awaits Thee is the seventh Christer Wijk murder mystery, so it comes fairly early in Lang's career which spanned from 1949 to 1990. If Death Awaits Thee is any indication of Lang's work as a whole then I'm afraid I'm not interested in reading any more as much as she has been recommended to me by a couple of people I've met at mystery conferences and in emails I've received. Those of you who read Swedish, of course, have all 43 novels to choose from. Those of us who only read English, however, have just three translations. The others are Wreath for a Bride, aka Kung Liljekonvalje av dungen (1957) and No More Murders, aka Inte flera mord (1951). The most recent editions of these three English translations released in 2014 are available only as digital books from Mulholland Books. Alternatively, you can spend half a lifetime as I did trying to track down older editions in paperback and hardcover. They seem to be disappearing as the years fly by. But if those too are the translated and Anglicized work of Joan Tate then it's further justification for avoiding the books.