Stephen Orlac is a concert pianist who is travelling back to Paris for a long awaited reunion with his devoted wife, Rosine. En route to the City of Lights the train crashes and there are multiple casualties. Rosine rushes to the scene of the accident and finds her husband under the body of a man clad entirely in white. The man in white later appears at various spots throughout the wreckage leading Rosine to dub him Spectropheles. This ghastly figure will continue to haunt her throughout the novel appearing and disappearing at the most unexpected places.

Unlike the man in white, Stephen has survived but has also sustained terrible injuries and must be rushed to a hospital for immediate surgery. He is operated on by Professor Cerral, a celebrity surgeon specializing in neurology and transplants. Stephen receives two hand transplants and his torturous recovery and attempt to regain his musical skills are the basis of the plot. Those who know the many movie versions know the secret of those hands and I'll not reveal it here. A fairly overused horror movie trope by now this gimmick of the hands seems to be an original idea of Renard's and he may be the first writer to use it in sensationalized genre fiction. The truth of Stephen's new hands is not revealed until the second half of the novel long after a variety of outrageous events occur ranging from ghostly manifestations, "externalized nightmares", an impossible jewel theft and the equally impossible return of the jewels to a safe in a locked rom, necromancy via a painted portrait as well as a seance complete with table tapping.

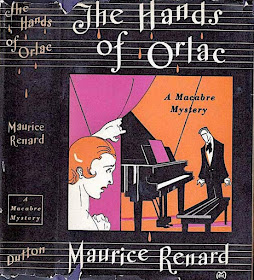

|

| Original French edition 1920 |

It is here that the influences of French pulp writers Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, creators of master criminal Fantomas, can clearly be seen. The first half of the novel subtitled "The Portents" has faint whiffs of the popular Fantomas serials so popular only five years prior to the publication of Renard's book. With its constant reiteration and recap of previous action and incidents the story bears obvious structural similarities to a serial and most likely did appear as one in a French newspaper or magazine. Central plot motifs like the ghost of a murderer being responsible for two deaths and the bizarre idea of a rubber glove bearing fingerprints of another person are two ideas that appear prominently in the third Fantomas serial published in book format in English as The Messengers of Evil (1911). Renard must have been familiar with that serial. He even includes a mythical gang supposedly behind all the criminal activity. His dangerous group, La Bande Infra-Rouge (The Infra Red Gang), is pure French pulp fiction. Apaches and murderous gypsies roamed the pages of French crime stories as much as Italian thugs and Irish gangs would appear in US pulp magazines. When Inspector Cointre, the egotistical policeman who seems entirely fashioned after Eugene Valmont, begins to fasten onto the idea of faked fingerprints all hope of the supernatural has pretty much been thrown out the window. Cointre has some of the best dialogue in the novel, too. After ripping apart a sofa and finding puppets and props that were used by the fake medium he expounds: "When dealing with mediums, never get you furniture re-covered, or at least keep an eye on your upholsterer."

At this point it is almost certain that the crimes, especially the murders, will appear to be the work of human hands and not spectral ones. Renard does what the French do so well in the earliest forms of detective fiction. He adds twist after twist. Stephen meets with the murderer who confesses his crimes. Then Renard dares to reveal that this being is in fact a walking dead man! But Renard is not finished with his twists until the final paragraphs when Cointre reveals the final solution to all the mysteries with an unexpected announcement.

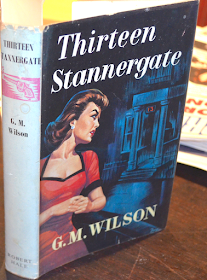

|

| Second English translation, the better one! (Souvenir Press/Nightowl Books, 1980) |

The most surprising element in the novel not seen in any adaptation I've watched is that Stephen's father, Edouard Orlac has become obsessed with spiritism. He and his friend Monsieur de Crochans have been dabbling in communicating with the dead. Though they are suspected of collaborating with fraudulent mediums and police are investigating their activities. In the climax of the first section one of the necromancy sequences seems to be genuine with a shocking surprise for Stephen when he spells out the name of the spirit they have contacted. And yet for all Renard's fascination with the macabre, the abundance of weird and paranormal activity, he is compelled to rationalize everything that occurred in the first half when he relates the second half entitled "The Crimes."

In the last chapters Rosine and Stephen face the inevitable and horrible truth, something the reader has most likely guessed at even if he has never seen nor heard of the several movie Orlacs. But a French detective novel has never been French without the ultimate surprise saved for nearly the final paragraph. When that gasper comes in The Hand of Orlac it is both satisfying for the reader and a godsend for Stephen and Rosine.