The crime novel plot motif of losing a corpse is often the basis for a black comedy romp. Craig Rice used this gimmick repeatedly in her novels featuring Jake & Helene Justus and John J. Malone, and it shows up in hundreds of movies notably Hitchcock's The Trouble with Harry. But in the hands of Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac a disappearing corpse is hardly a laughing matter. Celle Qui N'Etait Plus (1952) was the first collaboration between these two French writers who previously had both won French crime fiction awards for their solo efforts. The success of the duo's first book would lead to a long lasting friendship and over thirty more books as a writing team. In a nod to the novels of James Cain we get an avaricious, adulterous couple who drown the man's wife in a bathtub then manage to lose the body after dumping it in the lavoir (a French communal laundry near a river). It's a study in guilt, remorse and madness more than it is a detective novel. In fact, there is only one policeman who appears and he's a traffic cop who makes a brief cameo at the very start of the book. Boileau and Narcejac are more interested in the terror that resides within the mind of a guilt ridden murderer than they are the usual criminal investigation plot.

There is very little action in this book with most of the novel focusing on the thoughts and delirium of the main character. You may know the story from one of the several movie adaptations, but they are just that - adaptations. The film tells the story of two women drowning a husband while in the book a philandering couple murder the wife. The only things the book and the film have in common are a bathtub and the guilty imaginings of one of the killers. While the film takes a very different path to convey the terror of a guilt ridden mind with some indulging in horror movie motifs, the book is a bit more mundane in the way the same terror is depicted.

The main character in the novel is Fernand Ravinel, the husband. Fernand is an ineffectual travelling salesman who hawks sporting goods. His special talent is designing and creating fishing flies which take up an entire page in his company's fisherman's supply catalog. But Fernand is otherwise dull, unassuming and in frail health the result of a minor heart attack. He and his mistress Lucienne, a doctor, conspire to do in Fernand's wife Mireille and claim the insurance money. It is Lucienne who does the dirty work while Fernand unable to watch his wife being drowned in a bathtub leaves the room and listens to the murder being carried out. His only act as an accomplice drugging a beverage his wife drinks and fetching the andirons from the fireplace that will hold the body under water. It's a clinical murder carried out with the precision of a surgery. Later they transport the body to the Ravinel's home and unload her into the river that flows through the lavoir. When Fernand coaxes one of his bar mates to visit the lavoir under the pretense of assessing it for repairs he is shocked when his wife's body is no longer there. Thus begins his slow descent into a surreal world of strange events and morbid imagination.

There is an abundance of fog imagery throughout the novel. Boileau and Narcejac use this old Gothic novel trapping in a unique way. Since his childhood Fernand was obsessed with fog and used to play an odd game in which he disappeared into the fog, sort of an astral projection, where he sent his mind into the fog imagining that he has crossed over from the living to the dead. This idea of crossing over is further elaborated throughout the novel as Fernand tries to come to terms with whether or not Mireille is actually dead. She keeps turning up in their house leaving notes. There is even a report that she visited her brother though he was the only witness. The brother-in-law's wife resents that Mireille did stay long enough so she could see her too. This fact plants the seed in Fernand's mind that his wife may have been a ghost. Then he obsesses about a small detail -- Mireille kissing her brother's cheek. He wonders how the kiss felt, if it actually took place, or if Germain (the brother) was merely telling a story to make him jealous. Is she a ghost? Is she alive? If so, why does she not show herself to him? Did the murder take place or has he completely lost his mind?

There is a subtle suggestion that Mireille and Lucienne are the real adulterous lovers. Typical of the 1950s Lucienne is described as "mannish" and being stronger than Fernand. He cannot remember why he was attracted to her or what started their affair. A telling moment of his ignorance -- of his own life being enveloped in a thick fog of overlooking the obvious -- is when he finds photographs of a vacation the three took together. The pictures show Lucienne and Mireille smiling and joyful. Fernand is absent from them all. He cannot even remember taking the photographs himself. All he wonders is "Where am I? Why did no one take any photos of me?"

What little action there is comes in brief moments between Fernand and one other character. Very rarely are more than two people ever present in any scene. The novel is one of isolation. The real setting of the book is Fernand's mind. The story is almost exclusively made up of his thoughts, memories, reveries, and the "fog game". Boileau and Narcejac set the groundwork for their future crime novels centered on the aftermath of murder and how the criminal is in some ways more of a victim of his crime than the actual corpse. Like many of their best books this debut comes with one gut wrenching, shocking scene and a surprise twist in the final sentences.

She Who Was No More attempts to blend the conceits of a ghost story with a murder tale resulting in a claustrophobic, dreary world of doubt and mistrust. It is a loveless world with no real hope culminating in one of the most downbeat endings that rivals any American noir. French crime novels seem to be drenched in self-inflicted misery, more deeply affecting to the characters than the most violent crime.

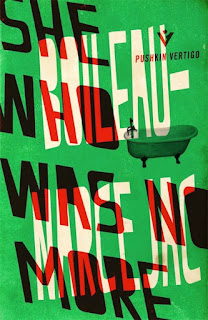

After decades being out of print and nearly all scarce paperback editions in English translation having being bought up by covetous collectors She Who Was No More is once more available in a new paperback edition from Pushkin Vertigo. They have reprinted the original 1954 English translation by Geoffrey Sainsbury (published as The Woman Who Was No More) rather than having a new edition translated. He does a fine job though he lapses into a stilted British idiom a bit too often. Nevertheless, fans of Boileau and Narcejac and those familiar with Les Diaboliques (or The Fiends), as it is known in the movie version, ought to grab a copy soon. Reading the novel is a revelation and an education into the beginnings of a writing team who unlike many lived up to the promise of their first book and proved to surpass this experimental crime novel with a handful of similarly groundbreaking work.

The only Boileau-Narcejac book I've ever managed to get hold is VERTIGO. Which is excellent so I'll keep a lookout for this one.

ReplyDeleteTerrific review of a marvellous novel. I'm amazed that so much of their work has never been translated into English.

ReplyDeleteTerrific post John - I have only ever seen the movie (which I love) and really had not realised how substantially it differs from the book - really fascinating, thanks chum.

ReplyDelete