"I am in one of my tempers tonight. I want a husband to vex, or a child to beat, or something of that sort. Do you ever like to see the summer insects kill themselves in the candle? I do sometimes."

-- Lydia Gwilt in Armadale (1866)

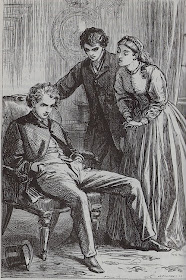

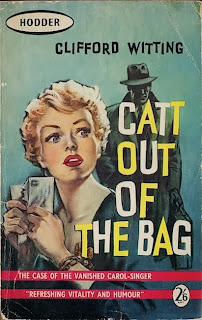

She has been called the most ruthless villainess in Victorian fiction, practically a prototype for the

femme fatale we all love to hate in film noir and paperback originals of the 1950s. With her fiery red hair, her caustic wit, her superficial charm, rapturous beauty, and her undying hatred of men she lives for cruelty and vengeance. She is Lydia Gwilt. Emotionally warped, spiritually bankrupt, psychologically ruined she is perhaps the most used and abused woman character Wilkie Collins ever created. But is she truly evil? By the novel's end most readers may find themselves shockingly feeling sympathy for Lydia's wrecked life and finding pathos in her final line "I was never a happy woman" as she meets her doom.

Replete with the worst of human behavior including murder, poisoning, bigamy, torture, fraud and all sorts of mental and physical cruelty

Armadale is the grand daddy of all noir fiction. The book can easily be seen as

The Woman in White (1860) in reverse. Whereas the earlier book has two women at the mercy of two scheming men out to win a fortune through deception and fraud

Armadale gives us two men being victimized by two plotting women both of whom are desirous of power and wealth and will stop at nothing to get what they want. In

Armadale the reader meets the unscrupulous Madame Maria Oldershaw and the vindictive, man hating Lydia Gwilt who serve as the female counterparts to Count Fosco and Sir Percival Glyde. Similarly, the light and dark characteristics, both physical and emotional, exemplified in Marian and Laura are mirrored in the portraits of Allan Armadale -- light haired, fair skinned, cheerful to the point of naivete -- and Ozias Midwinter -- his dark haired, swarthy opposite, a man of brooding darkness and superstition. This dichotomy of the two men is underscored by Collins in a chapter entitled "Day and Night."

Armadale opens with a deathbed confession. A dying man dictates the story of a past crime, a thwarted marriage, and a wicked servant girl's deeds that allow his fortune to fall into the hands of a man who shares his name. The confession taking the form of a lengthy letter addressed to his son concludes with a warning that his son is to avoid at all costs a man named Armadale and the servant girl who he feels caused all their misery. The letter is delivered to the family lawyer with instructions that it be given to his son when he is old enough to understand the horrible story. Thus the seeds are planted for a tale of Fate and doom and the question of whether chance can really exist.

Despite his father's warning of dire peril that will befall him Midwinter meets Allan Armadale and is almost immediately his bosom friend. Allan, the good natured one, has a series of strange dreams that he relates to Midwinter that will have an eerie hold over the fearful youth who believes wholeheartedly they are dreaded omens. He does his best to prevent the dreams from becoming fulfilled prophecies. Yet as each segment of the dream comes true he feels more and more that he has made a fatal mistake by befriending Allan and not following his father's instructions. With the entrance of Lydia Gwilt the story becomes one of three lives destined to be inextricably entwined.

As with most of Collins' novels the book is made up of multiple viewpoint narratives, letters and diaries. When the focus is on Midwinter the novel delves into a near supernatural realm with his obsession with Allan's dream and the inescapable thought that he has no control over what appears to be a doomed and very short life. But when the book is told from Lydia's viewpoint it attains the most chilling moments, the most cynical observations and paradoxically its most poignant scenes. She also has the best lines in which Collin's displays a wicked sense of humor.

|

| Lydia Gwilt and the "Gorgons" |

"There are occasions (though not many) when the female mind accurately appreciates an appeal to the force of pure reason."

"She looked at the ground with such an extraordinary interest that a geologist might have suspected her of scientific flirtation with the superficial strata."

"Half the musical girls in England ought to have their fingers chopped off, in the interests of society -- and, if I had my way, Miss Milroy's would be executed first."

"I am sadly afraid the man is in love with me already. Don't toss your head and say, 'Just like her vanity!' After the horrors I have gone through, I have no vanity left; and a man who admires me, is a man who makes me shudder."

"Did you ever see the boa constrictor fed at the Zoological Gardens? They put a live rabbit into his cage, and there is a moment when the two creatures look at each other. I declare Mr. Bashwood reminded me of the rabbit!"

"After bewildering himself in a labyrinth of words that led nowhere, he took her -- one can hardly say round the waist, for she hasn't got one -- he took he round the last hook-and-eye of her dress..."

"Am I mad? Yes; all people who are as miserable as I am are mad. I must go to the window and get some air. Shall I jump out? No; it disfigures one so, and the coroner's inquest lets so many people see it."

Lydia may be the star of the novel but she does not completely overtake the stage as villain supreme. Madame Oldershaw has just as many moments of wry and bitchy humor and a few cross purposes to boot. To watch the decrepit and fawning Mr. Bashwood, errand boy and spy, fall in love with Lydia is to view a portrait of bathos and creepiness. By the novel's finale he may remind one of Victorian fiction's male equivalent of Miss Havisham. The unctuous Dr. Downward appears in the final section of the book and proves to be quite a match for Lydia. Finally, Captain Manuel, a man from Lydia's secret filled past, nearly outdoes her in nastiness.

|

| Pedgift , Sr. |

On the other hand there are also some finely drawn supporting characters on the side of our manipulated heroes. Reverend Decimus Brock is Allan's guardian and Midwinter's confidante, the man who for over three quarters of the book is the only one privy to Midwinter's secret identity and his haunted past. Among my favorites is Augustus Pedgift Sr., a wise lawyer who attempts to advise Allan Armadale of his folly in keeping a friendship with Lydia. When Pedgift is featured the novel shows clearly how well Collins engineers suspense and reveals Lydia's true character. A pity that Armadale is so infuriatingly naive and cannot see what to everyone else is so obvious.

For a prime example of Victorian Sensation at it most lurid and thrilling look no further than

Armadale. Collins pulls out all the stops in this novel incorporating supernatural elements, trenchant humor, bitter cynicism, genuine suspense and dizzying plot twists. You'll pray for the heroes and condemn the villains. But by the novel's inevitable conclusion you may be surprised by your feelings for one of Victorian literature's most splendid of wicked women. Lydia Gwilt, you may learn, may not be all that bad after all.

* * *

This is my first book in the

Vintage Mystery Reading Challenge sponsored by Bev at

My Reader's Block. I've assigned this book the spot I call D1 ("An Author I've Read Before") on the Golden Age Bingo Card. Only 35 more to go on this card. Oy!